Objects and stories

Objects are an important part of the Nobel Prize Museum's physical and digital exhibitions. Here you can explore the objects and the stories about them.

The Nobel Prize Museum's objects primarily reflect the different areas of the Nobel Prize and the activities, interests and personalities of the Nobel Prize laureates. They also shed light on Alfred Nobel and his activities, as well as the various procedures surrounding the Nobel Prize.

The objects have varying origins, but most of them have been donated to the museum laureates themselves or their families. Some ended up in the museum in other ways.

-

Photograph (replica)The image is a copy of a rarely reproduced photograph of Santiago Ramón y Cajal as a young man. The image was donated to the Nobel Prize Museum by Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s family in 2025.

-

Printing blockThis wooden printing block bears an illustration of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. It is probable that he not only executed the original drawing but also engraved the image into the block himself. Commissioning such work from a professional engraver was costly, so Cajal learned the craft of engraving the image into the wood. The block is made of boxwood, which is very hard and lacks distinct growth rings. The illustration depicts a cross-section of the midbrain of a newborn mouse. The section is a sagittal cut—a vertical slice that divides the brain into a left and a right side. The printing block was donated to the Nobel Prize Museum by Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s great-grandson, Ángel Cañadas Bernal, in 2025. He presented the gift on behalf of the family.

-

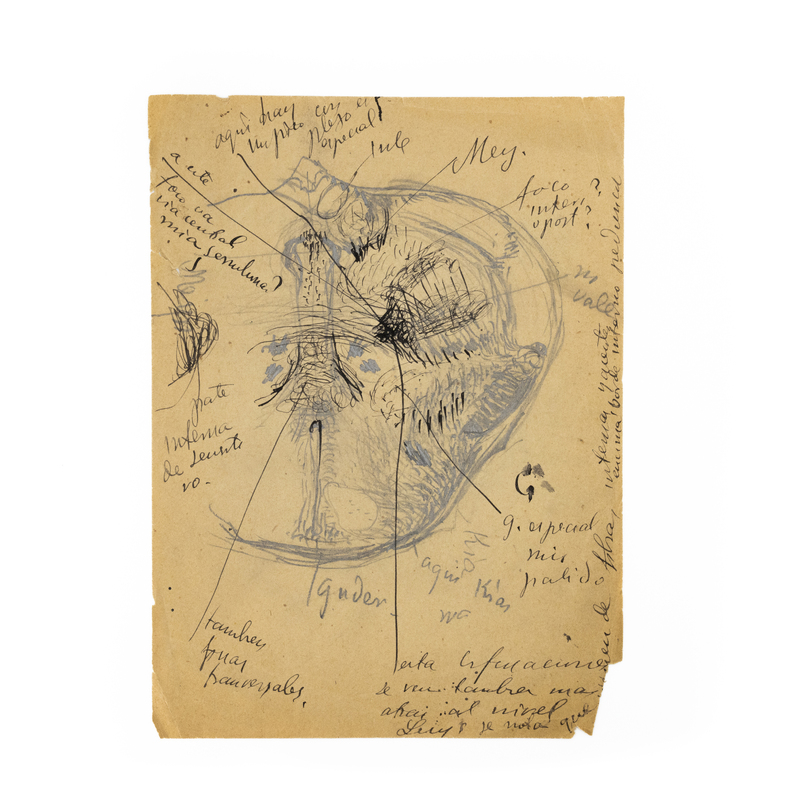

DrawingThis drawing is a preparatory sketch for an illustration in one of Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s scientific works on the brain and nervous system. The image shows a vertical cross-section of the thalamus, a part of the midbrain, in an eight-day-old mouse. Ramón y Cajal created his images after studying a thin slice of the brain under a microscope. To make the nerve cells visible, Cajal stained them using a method developed by Camillo Golgi, who shared the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Cajal. After the preparatory drawing, he produced a clean, finalized version that was used for the printed image in the scientific work. Ramón y Cajal’s images are characterized by clarity, precision, and rich detail, demonstrating great artistic talent. In his youth, Ramón y Cajal wanted to become an artist but was encouraged by his family to pursue medicine. His artistic skill and interest proved invaluable in his exploration of the brain, the nervous system, and its various types of cells. The drawing was donated to the Nobel Prize Museum by Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s great-grandson, Ángel Cañadas Bernal, in 2025. He presented the gift on behalf of the family.

-

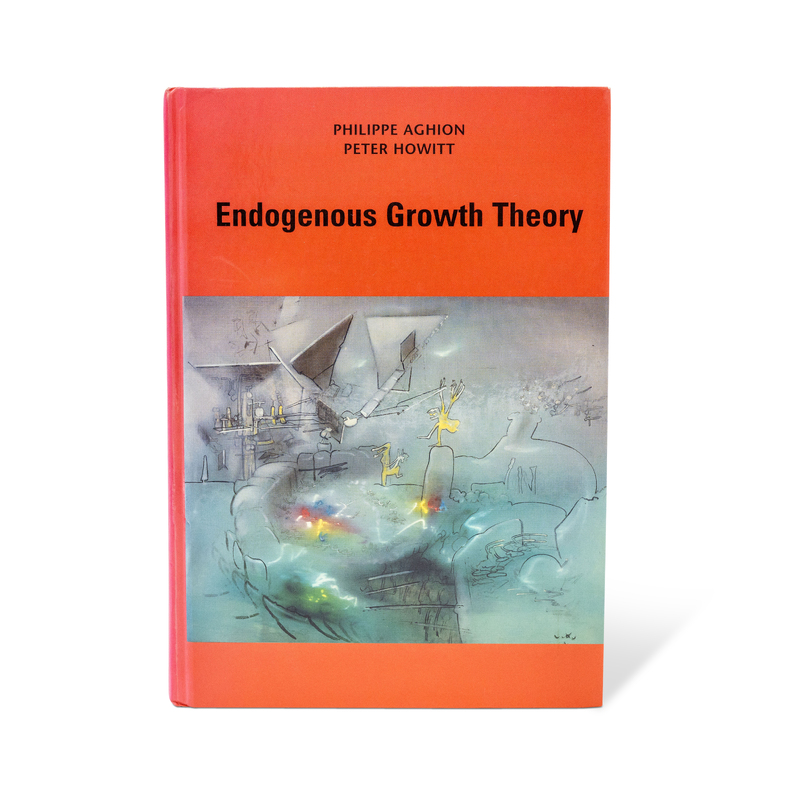

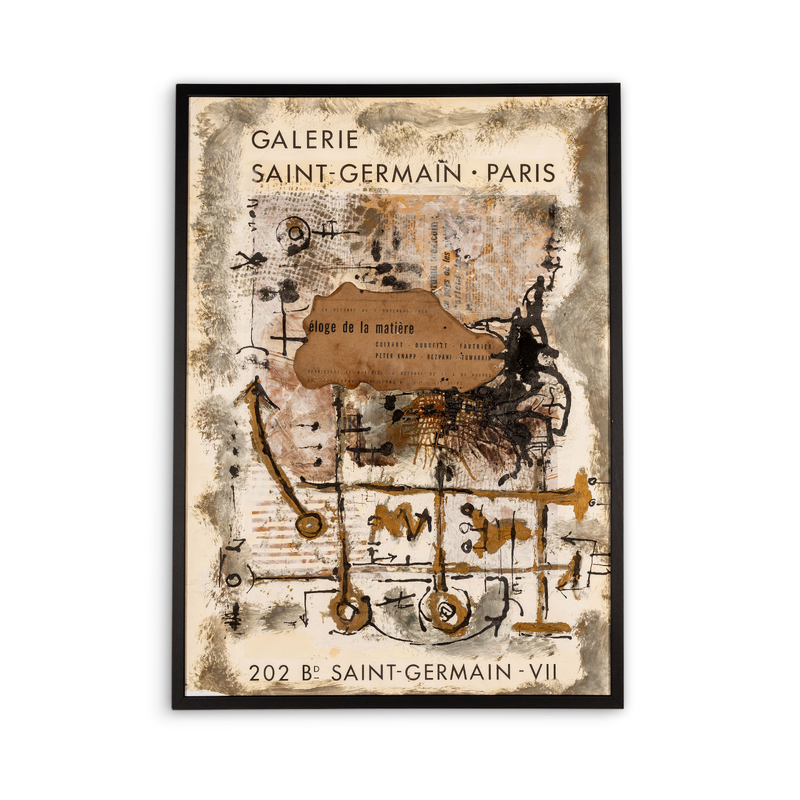

AffischThis poster presents an art gallery that was run by Phillippe Aghion’s father, Raymond Aghion in 1956–1966. The gallery was in Saint-Germain-des-Près in Paris, a neighbourhood with a vibrant art scene. The family moved in artist circles. The names of some of the artists who exhibited at the gallery are featured on this poster. It was designed by the Israeli artist Igael Tumarkin around 1960. Tumarkin believed it was crucial with a dialogue between Israel and Palestine, and Aghion shared his opinion. Aghion’s parents were both from Jewish families in Alexandria, Egypt, and moved to Paris when they were young. His mother, Gaby Aghion, became a famous fashion designer and founded the Chloé label. His father, Raymond, was a politically active communist and worked for a social revolution in his native Egypt. One of his aims was that everyone should have access to new technology, in a better and more equal society. Technological development and economic growth are what Philippe Aghion’s research is about. Phillippe Aghion donated this poster to the Nobel Prize Museum in 2025 as a tribute to his parents.

-

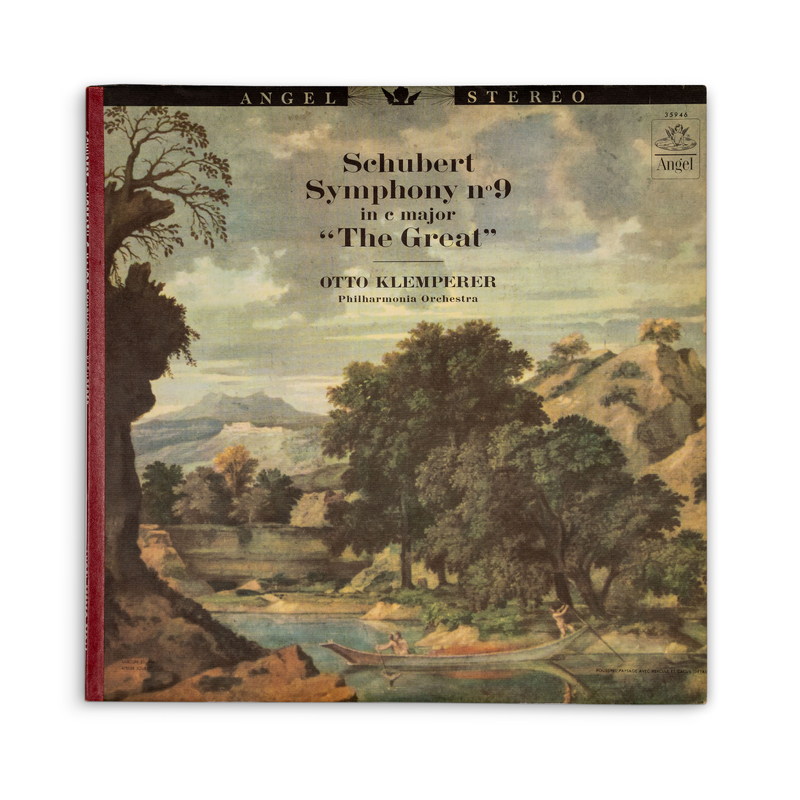

LP recordJoel Mokyr bought this record when he was 15. It was the first LP he ever bought, and he still thinks Schubert’s ninth symphony is among the most perfect pieces ever composed. The recording of the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Otto Klemperer is from 1962, and Mokyr considers it to be the best one ever made. The album also serves to illustrate Mokyr’s research into how new technology makes old technology obsolete. We can now listen to the music on digital streaming services instead of on vinyl and CDs. Joel Mokyr donated the LP to the Nobel Prize Museum in 2025.

-

NetsukeLászló Krasznahorkai has made numerous trips to China and Japan and written several stories that are set in Japan. On one of his visits, he bought this netsuke, a Japanese miniature sculpture, which has been very important to him. The netsuke represents a wise old man. The wise man is very calm. The artist has not portrayed him as someone who is contemplating. Instead, he seems to be beyond thinking, since there is no longer any reason for him to think. To be at one with existence is sufficient for him, and this is why the wise man is so peaceful and happy. This also gave Krasznahorkai new insights. After writing his novel War and War, Krasznahorkai experienced a personal crisis and thought he could never write again. Without the wise man, he could never have resumed his writing. A netsuke was originally a kind of button – it was used to hold clothing such as kimonos together. From the 19th century, netsukes became more ornately crafted. It is not entirely easy to identify the artist who made this netsuke, since several artists worked under the name of Mazakasu. But the originator was probably Mazakasu Sawaki, who was born in Nagoya but lived and worked in Osaka for most of the late 1800s. Krasznahorkai bought the netsuke from the artist’s family. László Krasznahorkai donated the small figurine of the wise man to the Nobel Prize Museum in 2025, thanking the museum for keeping it safe even when he is no longer alive. “It is so vulnerable, so small. It can be lost, it can be broken. But if it can remain here, I will be at peace.”

-

ShoesFor Fred Ramsdell, these shoes are linked to a special memory. Here is his story: “So, there I was, on the last day of a nearly 4-week camping trip. We’d just driven through Yellowstone National Park and had stopped the truck at an unoccupied campground to let the dogs wander around a little. As we neared ‘civilization’, my wife Laura checked her phone for the first time in over a week. And then she begins to cry out. I’m wondering what’s going on – and she comes out with a big grin and tells me I’ve won the Nobel Prize. I honestly didn’t believe her at first, but then, it was abundantly clear that I had, in fact, won the Nobel Prize. I was wearing these shoes when she told me – I’d been wearing them virtually every day for the past 4 weeks. We’d hiked hundreds of miles and driven hundreds more. We get into the mountains as often as possible, but almost always take an extended trip in September when most people have gone back to work or school. It’s a way for me to look at life, including science, from a different perspective. Back in the days when we were trying to identify and characterize the scurfy mouse, we would backpack regularly (we had younger dogs back then). Scientific progress is often a painstakingly slow process, with many false steps and delayed gratification. It’s a wonderful career, but it can also be extremely frustrating. Being able to get out of my own head helps me ‘recharge’ and sometimes see a problem from a new perspective. Hiking rarely leads to any scientific breakthrough, but, like science, it feeds my soul.” (Scurfy mice have scaly skin, caused by a genetic defect that causes a lack of regulatory T cells. Scurfy mice were crucial to the research that led to Fred Ramsdell and Mary Brunkow receiving the Nobel Prize.) Fred Ramsdell donated the shoes to the Nobel Prize Museum in 2025.